Stuck in Fiji Mud welcomes Dr Ratuva's honest assesment of Fiji's political situation and would anticipating more.

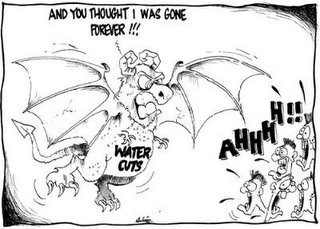

Fiji's water situation is getting to a point beyond embarassing.

So is the trade imbalance statistics despite the usual lip service of navel gazing.The under currents of resent between Qarase's cabinet and Fiji Army Commander is simmering again.

Officers, gentlemen and coups: Civil-military crisis in Fiji

By Dr Steven Ratuva

Dr Steven Ratuva

The recent “showdown” between the military commander, Commodore Frank Bainimarama, and former Land Forces Commander, Colonel Jone Baledrokadroka, fundamentally boiled down to an issue which has been the centre of contention in many countries: Where do we draw the line between civil state governance and the professional military?

Fiji is not alone in this. Military forces in almost every post-colonial state in the world have been faced with the dilemma of trying to make this separation clear and operational. Chile struggled for a long time since the military coup in 1972 to professionalise the military and bring it under civilian state governance. Since liberation in 1994 the South African military, which was nurtured under a repressive apartheid system, had to go through fundamental ideological transformation to fit into the new democratic mode.

Countries like Argentina, Ghana, Nigeria, etc. with histories of military coups have attempted, with certain degrees of success, to ensure harmonious institutional relations between the civilian government and the military. On the other extreme, some countries like Myanmar (Burma) and Pakistan, which have been under direct military rule, are still struggling to come to terms with democratic civilian governance.

Why is Fiji still faced with this dilemma? Why is the line between democratic governance and the military institution still contested?

A transforming military

The 2000 coup was a turning point in the evolution of the Fiji military. Since its establishment in the 1800s the military’s role has largely been for the purpose of “internal security”. It was used by the colonial state during the early years of British colonial rule for the purpose of “pacification” to maintain its dominance and by independence “ownership,” so to speak, shifted to the new ruling indigenous Fijian establishment.

The ruling indigenous Fijian elites saw the military as its security apparatus to defend their interests and even within the military there was an embedded assumption that the military was a guardian of Fijian rights. This was expressed in a violent form a month after the April 1987 election when the military, under then Lt-Colonel Sitiveni Rabuka, intervened on behalf of the indigenous Fijian establishment after the defeat of the Alliance Party, the major indigenous Fijian political party, in power since independence in 1970.

Since the 1987 military coups the military went through phases of transformation, including change in leadership. Brigadier Ratu Epeli Ganilau took over from Major General Sitiveni Rabuka and Commodore Bainimarama took over from Ganilau. Bainimarama’s appointment was seen as an attempt to de-politicise the military.

By allowing the Fiji military to be used to serve ethno-nationalist political interests, Rabuka had transformed it into a “political army.” This was a moral burden which the military had to unpack and exorcise, and it did so with efficiency and professionalism during the 2000 coup. Ethno-nationalist political agitators who hoped to use the military again as a political tool like in 1987 failed and the consequences were disastrous for them.

The military by then had, to some degree, evolved ideologically into a non-partisan, non-ethnic praetorian institution under the leadership of Frank Bainimarama. To many Frank became a hero and saviour, whose courageous and steadfast stance saved the country from sliding down the abyss of chaos.

However, this is where the problem started. The newly-elected government under Prime Minister Qarase, had an ethno-nationalist stance and was perceived by the military to be sympathetic to the coup perpetrators, even to the extent of forming a coalition with their party, the Conservative Alliance Matanitu Vanua (CAMV).

This directly undermined Frank’s desire to cleanse the country of coup makers to ensure that a coup culture does not emerge in the future. This directly led to confrontation, tit for tat verbal exchange over security and governance issues and consequently leading to a “cold war” of sorts between the military and the government.

The government could not keep up with the tempo and resorted to self-inflicting punishment by replacing the CEO and Minister for Home Affairs. This was victory for Frank who may have assumed that since he saved the country from chaos in 2000 and since he gave Qarase the “mandate” to rule Fiji as interim PM, he still had the moral right to share - and if possible impose - his views on leadership with the government.

The tension worsened with the introduction of the Reconciliation and Unity Bill, which the government had hoped would settle the post-coup reconstruction and reconciliation processes once and for all, even if it meant providing amnesty to coup perpetrators like George Speight.

Then came the differences over the court martial in which a number of former soldiers were being tried for their part in the November 2 2000 mutiny, at the Queen Elizabeth Barracks in Suva. The delay with which the government dealt with the appointment of the Judge Advocate convinced Frank that a conspiracy to sabotage the trials was in the air.

Coup threat

At this point the built up tension was on the verge of exploding. Frank threatened to “remove” the government - or in other words, stage a coup. This sent shockwaves throughout the country and beyond. Worst still, it would have shocked his own senior officers and rank and file soldiers who have been conditioned to believe that the military was no longer in the business of staging coups.

Coming from someone who had been hailed a “coup breaker” the threat did not seem to make sense to many. Staging a coup to avoid future coups appeared to be an illogical proposition to say the least. A coup, however noble the intentions were, was still a coup and a coup was tantamount to the illegal overthrow of a democratically elected government, no matter how “corrupt”, “racist” or unpopular the government may have been.

Frank versus John

This is the backdrop to the standoff with John Baledrokadroka. John is a young and highly-trained officer with a Master of Arts degree in Strategic Studies from the Centre for Defence and Strategic Studies (CDSS) in Canberra, where I met him while I was an invited visiting lecturer on security studies there while working at the Australian National University. Some senior officers went through the comprehensive training regime at CDSS, an internationally-reputable senior officer training institution.

Their training in the art and dynamics of the modern military, state security and civil-military relations and their extensive international operational experience would have shaped their views and dispositions on the role of the military in a modern state.

That in an ideal situation, there should be a respectable line of demarcation between the civilian authority and the professional military. Part of the re-professionalisation process within the military since 2000 was precisely to achieve this, to ensure that the military was not going to be used again for any political purpose as was the case in 1987.

For the new breed of professional officers, the last thing they would want to hear was the word “coup”, especially when it would compromise the political neutrality of the military as well as being outright illegal and treasonous. Given this situation, Frank’s take over threat was the last straw for someone like John. Frank, they would have imagined, had crossed the line and in the process may have compromised the professional status of the military.

Support for Frank during the 2000 coup came from officers like John who led the assault which freed the military camp from the mutineers. John was a very articulate soldier who was not afraid to express his views publicly via the letters to the editor column regarding his analysis of politics in Fiji and disdain of ethno-nationalist ideologies and bad governance.

His attempt to restrain Frank led to a showdown and ultimately his downfall. A coup, no matter what the justification was, would have destroyed the integrity of the military once and for all, tarnished Frank’s good reputation as hero of 2000 and destroyed the country in unimaginable ways.

Moreover, the question is whether Frank’s takeover threat was serious or whether it was simply a psychological coercion strategy to put pressure on the government. As I told foreign journalists who interviewed me, I did not believe that a coup was going to take place because I trusted that Frank and his senior officers were fully aware of the implications. But nevertheless the threat itself was enough to cause mayhem.

If Frank was serious and actually hoped to carry out a coup, would he be able to mobilise the support and loyalty of his officers? Torn between the twin serious crimes of treason and mutiny, what would his senior offices choose? Would we be staring at a situation worse than 2000? Fortunately the situation in the military stabilised quickly and Frank quickly reasserted control.

Another question is whether John was influenced by outside political forces. This is still being investigated. Perhaps he may have been in discussion with various people about politics in Fiji as any other person would do but that does not take away the fact that John had a very deep commitment towards values of good governance, apolitical military and professionalism which I believe would have been the biggest ideological and intellectual force behind his resolve.

Both Frank and John believed deeply in the reprofessionalisation of the military, re-democratisation of the country and rounding up and punishment of the 2000 coup perpetrators but their differences revolved around their different approaches.

Frank advocated a more politically proactive approach involving putting pressure on the government to speed up the prosecution process. John believed in achieving the same end but using strictly apolitical means. This was where the two good friends diverged and, sadly, parted company.

Other senior officers would no doubt support Frank’s commendable effort in bringing the coup perpetrators to justice but some may not fully endorse some of his overtly political approaches in private, but will continue to show loyalty anyway.

Resolving the dispute

The best way to resolve the ongoing dispute is to engage in deep and mutual dialogue not only about issues but also about our institutions of governance, governance processes and the lines of responsibilities, especially between the civil state and the military. One should not assume that the lines are obvious and people know where they are.

Government should develop a more consultative approach to policy formulation and the military should be mindful of the way it engages with the government so that it does not unnecessarily impinge on the process of political governance. Inability to create and maintain this balance can lead to instability.

As part of the broader consultative approach we really need to put in place a broad-based security partnership process consisting of the military, police, ministers, civil servants, civil society organisations, research institutions, community representatives, worker representatives, youth and women representatives and political parties to engage in dialogue about security matters.

At the moment the National Security Council only consists of members of Cabinet. Security is everyone’s business, not just of government ministers and so everyone must be involved in particular ways.

For Frank, it would be of great help to him if he engages his senior officers more through mutual consultations and frank discussions on important issues. This would iron out potential differences with his officers and consolidate solidarity within the army considerably. It must not be seen to be aligning itself with a particular political party.

Political parties should be more sensitive and must stop unscrupulously riding on the back of the crisis for opportunistic political gain, either in support of the military or government because in doing so they simply worsen the crisis. They must instead use their potential to look for solutions.

The dialogue between Frank, Qarase and the Acting President, Ratu Joni Madraiwiwi was exemplary of how cool-headedness and reason can overcome emotion, although there is a view that the compromise may have shifted the constitutionally prescribed lines of accountability between the military and the government and in the process strengthened the commander’s position significantly. However, if this leads to stability then this may be appropriate in the short term, but in the long run, we really need to carry out serious re-examination of our governance institutions and processes to ensure that the government can carry on with the business of governing without duress, the military can carry on with the business of maintaining security in a professional way as it has been superbly doing and citizens can carry on with their daily lives in peace.

After all when things go wrong the country as a whole suffers. As the African idiom philosophically pronounces: “When two big elephants fight, the grass suffers.”

Dr Steven Ratuva is a political sociologist at the University of the South Pacific.

Club Em Designs

No comments:

Post a Comment